Non-Periodic Phenomena in Variable Stars

IAU Colloquium, Budapest, 1968

SUDDEN CHANGES IN THE PERIOD OF ALGOL

T. HERCZEG

Hamburg - Bergedorf

(Read by W. Seitter)

Orbital motion in binary systems was considered, for a long time, a true

paradigm of periodic phenomena. Even its occasional changes were

supposed to be of strictly regular, i.e. periodic nature like rotation

of the apsidal line or light time effects in multiple systems.

Exceptional objects like beta Lyrae, with a secular increase of the period,

could have been recognized as cases still showing some regular,

predictable character. Later on, however, after longer series of

observations became available, a sort of eclipsing systems (like XZ And)

were found showing obviously non-periodic changes of the period: an

erratic but continuous up and down in the O-C diagrams for the times of

minima. Other well observed photometric binaries exhibited a different

type of non-periodic changes: the eclipsing period was, from time to

time, subject to sharp sudden changes ("jumps") while between two

consecutive jumps it remained practically constant. AR Lacertae or AH

Virginis are important examples of this type.

Schneller (1962) in a lecture at the Budapest Observatory advocated his

thesis that, while "regular" changes of the eclipsing period are

relatively infrequent, these sudden, erratic changes seem to be the

rule, at least in the case of the contact and semi-detached systems.

Among other typical objects he mentioned Algol (beta Persei) itself

- certainly one of the best observed variables - as indicating period

changes of this nature; a similar proposal concerning Algol's period, as

a matter of fact, was already put forward by Sterne.

In the case of Algol, Schneller tried to represent the O-C curve of the

times of minima by a polygon having two angles, two "sharp bends". They

correspond to sudden changes, discontinuities of the period, having

occurred in 1840 and 1924. This proposal has been essentially

substantiated by a recent analysis of all photoelectrically determined

epochs of minima, carried out at the Hamburg observatory (cf. a forthcoming

paper by Frieboes-Conde, Herczeg and Hog). In particular, the occurrence of

"period jumps" seems to be definitely established now though numerical details

(like the data of these changes) had to be revised.

This interpretation of the O-C curve offers us an explanation of the

much discussed "great inequality" of Algol, too. This is a hypothetical

long period light time effect requiring the existence of an additional

unseen companion (Algol D) in the system. Up to now there are three observed

and, at least, two hypothetical members listed as belonging to the complicated

Algol system. Those observed, definitely recognized components are:

Algol AB the eclipsing pair, a semi-detached system;

Algol C, a distant companion with a period of 1.862a. This orbital motion

in the triple system gives rise to a light time effect of the times of

minima; having a small amplitude (~~ 6 min.), it is rather difficult to

handle. On the other hand, there exists an accurate and reliable set of

spectroscopic elements for this 1.9 year orbit, derived by Ebbighausen (1958).

The hypothetical members are:

Algol E, introduced for explaining by light time effect a clearly

distinguishable 32-year periodicity of the O-C values by light time effect.

This periodicity can be, however, much more convincingly explained by the aid

of apsidal motion in the eclipsing system;

Algol D, a component proposed already in the last century in order to

find an explication for the above mentioned great inequality, dominant

feature of the O-C diagram, with a suggested period of about 170-180

years. But an interpretation of the great inequality as a light time

effect faces also serious difficulties. Until now, the periodicity

itself defied exact representation: predictions based upon a recent,

very elaborate discussion of the period changes by Kopal, Plavec and

Reilly (1960) yielded residuals amounting to half an hour. Besides, the

mass of this hypothetical unseen companion turns out to be unexpectedly

high, about 4 M_Sun. A further important question is the following: a

possible light time effect would require an orbit large enough to cause

detectable changes (> 1 sec of arc) in the position of Algol AB, a much

observed 2nd magnitude star.

Our discussion of all meridian observation reaching back to about A. D.

1750 indicated, however, that Algol's proper motion remained sensibly

constant - no traces of the orbital motion in the hypothetical quadruple

system Algol ABC-D could be found. This seems to be a direct and decisive

argument against the existence of the component Algol D.

We are now obliged to find an alternative explanation for the great

inequality. Let us make the basic assumption that - besides the eclipsing

period, the 1.9-year light time effect and the 32-year period - no further

periodicities exist in the O-C diagram. (This assumption, which might be

opposed by some observers, has turned out a very useful and also successful

working hypothesis.) Then a rather sensitive test can be carried out, based on

the best determined, photoelectrically observed epochs of minima, about 60

in number since 1920. We treated this rather accurate observational material

in the following way:

We subtracted the effect of 32-years periodicity. This correction was

based on data by Hellerich (1919);

We accepted as a definite representation of the 1.862a orbit the spectroscopic

elements given by Ebbighausen (1958, 1962). Thereafter, the corresponding light

time effect can easily be taken into consideration.

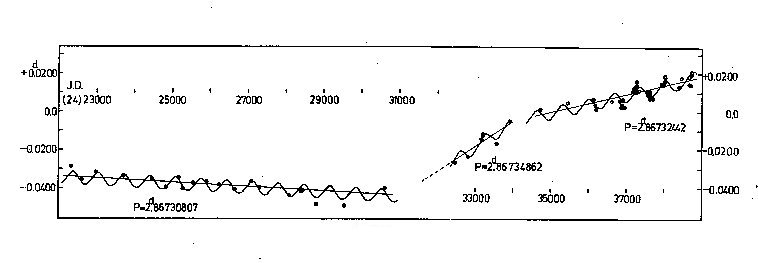

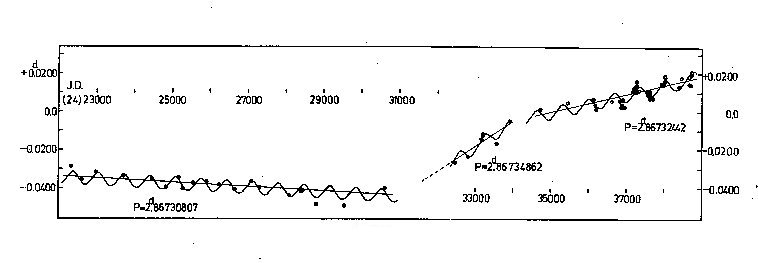

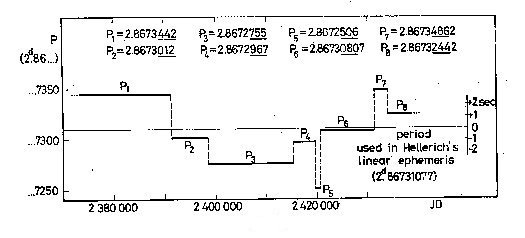

Then the residuals have shown with considerable accuracy a polygon indicating

two sudden changes of the period (in 1944 and 1952) and three different values

of a practically constant eclipsing period outside these "jumps" (Fig. 1).

The sudden changes amount to Delta P = +3.5s and Delta P = -2.0s, respectively.

The constancy of the period within the time intervals, say 1920-1942 and

1955-1965 can be judged from the good representation of the 1.9-year light

time effect, the remaining scatter of the O-C values being but slightly higher

than the usual error of photoelectrically determined epochs of minima. It seems

very improbable that any further periodicities could be accomodated within

this small margin.

Fig. 1

The reliability of Hellerich's numerical representation of the 22-year

period is, of course, a basic question. Though small systematic deviations are

not to be entirely excluded, no serious error can, - in my opinion - arise

hereby. Especially the fact that the two jumps are rather close together,

separated by a quarter of the period only, means that the existence of

two sudden changes remains incontestable.

This somewhat perhaps surprising representation of the photoelectric

times of minima encourages me to an experiment: to apply a similar

procedure to the earlier measurements, too. Minima were observed since

1784 in a very great number. The overwhelming majority of these times of

minima is based on visual estimates, and their rather modest accuracy

(of the order of +-0.02d), doesn't permit a detection of the 1.9-year

light time effect. Besides, the in fluence of minor systematic errors in

the representation of the 32-year period will be considerably enhanced

by going back to the 18th century observations. This makes our proposed

representation to a tentative one; on the other hand the deviations from

a reasonable picture turn out relatively small, thus suggesting the

proposal I am going to discuss is not completely arbitrary.

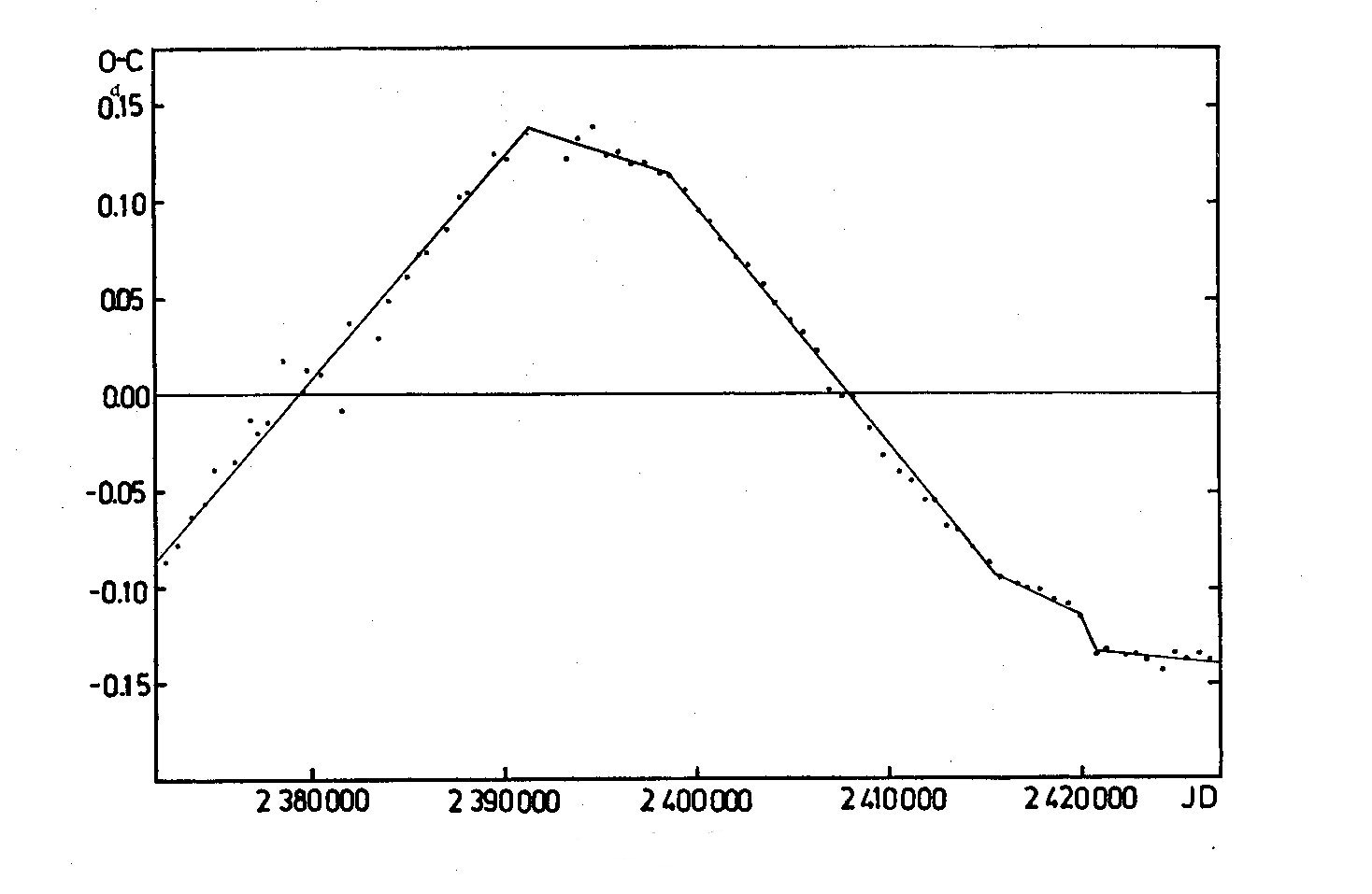

Because of the large scatter of the individual epochs I used the normal

points meticulously derived by Ferrari (1934). Again, I subtracted Hellerich's

formula for the 32-year term. The residuals not only allow, they clearly

suggest a representation given by a polygon. The representation derived earlier

from the photoelectric minima is a continuation of this new polygon - the long

interval of constant period 1920-1944 can well be extended back to 1915.

There is no indication of a sudden period change in 1924 as it was proposed

by Schneller; the short sharp change around 1914/15 seems to be real (Fig. 2).

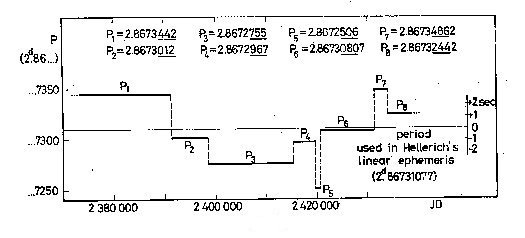

The following table summarizes this possible sequence of "events":

P_1 = 2.8673442d (1784)- 1835 (approx.) Delta P ~~-3.7s

P_2 = 2.8673012d 1835 - 1854 ~~-2.3s

P_3 = 2.8672775d 1854 - 1901 ~~+1.7s

P_4 = 2.8672967d 1901 - 1913 ~~-4.0s

P_5 = 2.8672506d 1913 - 1915 ~~+5.0s

P_6 = 2.86730807d 1915 - 1944 ~~+3.5s

P_7 = 2.86734862d 1944 - 1952 ~~-2.0s

P_8 = 2.86732442d 1952 -(1965)

Fig. 1

The reliability of Hellerich's numerical representation of the 22-year

period is, of course, a basic question. Though small systematic deviations are

not to be entirely excluded, no serious error can, - in my opinion - arise

hereby. Especially the fact that the two jumps are rather close together,

separated by a quarter of the period only, means that the existence of

two sudden changes remains incontestable.

This somewhat perhaps surprising representation of the photoelectric

times of minima encourages me to an experiment: to apply a similar

procedure to the earlier measurements, too. Minima were observed since

1784 in a very great number. The overwhelming majority of these times of

minima is based on visual estimates, and their rather modest accuracy

(of the order of +-0.02d), doesn't permit a detection of the 1.9-year

light time effect. Besides, the in fluence of minor systematic errors in

the representation of the 32-year period will be considerably enhanced

by going back to the 18th century observations. This makes our proposed

representation to a tentative one; on the other hand the deviations from

a reasonable picture turn out relatively small, thus suggesting the

proposal I am going to discuss is not completely arbitrary.

Because of the large scatter of the individual epochs I used the normal

points meticulously derived by Ferrari (1934). Again, I subtracted Hellerich's

formula for the 32-year term. The residuals not only allow, they clearly

suggest a representation given by a polygon. The representation derived earlier

from the photoelectric minima is a continuation of this new polygon - the long

interval of constant period 1920-1944 can well be extended back to 1915.

There is no indication of a sudden period change in 1924 as it was proposed

by Schneller; the short sharp change around 1914/15 seems to be real (Fig. 2).

The following table summarizes this possible sequence of "events":

P_1 = 2.8673442d (1784)- 1835 (approx.) Delta P ~~-3.7s

P_2 = 2.8673012d 1835 - 1854 ~~-2.3s

P_3 = 2.8672775d 1854 - 1901 ~~+1.7s

P_4 = 2.8672967d 1901 - 1913 ~~-4.0s

P_5 = 2.8672506d 1913 - 1915 ~~+5.0s

P_6 = 2.86730807d 1915 - 1944 ~~+3.5s

P_7 = 2.86734862d 1944 - 1952 ~~-2.0s

P_8 = 2.86732442d 1952 -(1965)

Fig. 2

This interpretation decomposes the great inequality into a series of

sudden period changes. Apparently they are forming a random set, the

changes occurring on an average once in 25-30 years. This is certainly a

non-periodic phenomenon, probably caused by discontinuities of the mass

exchange between the components or in the mass loss from the whole

system. Perhaps, the "overflowing" of the secondary component of its

Roche-limit is not a smooth phenomenon but it causes from time to time

directional outbursts of mass from the secondary, hereby changing the

eclipsing period in a sudden way.

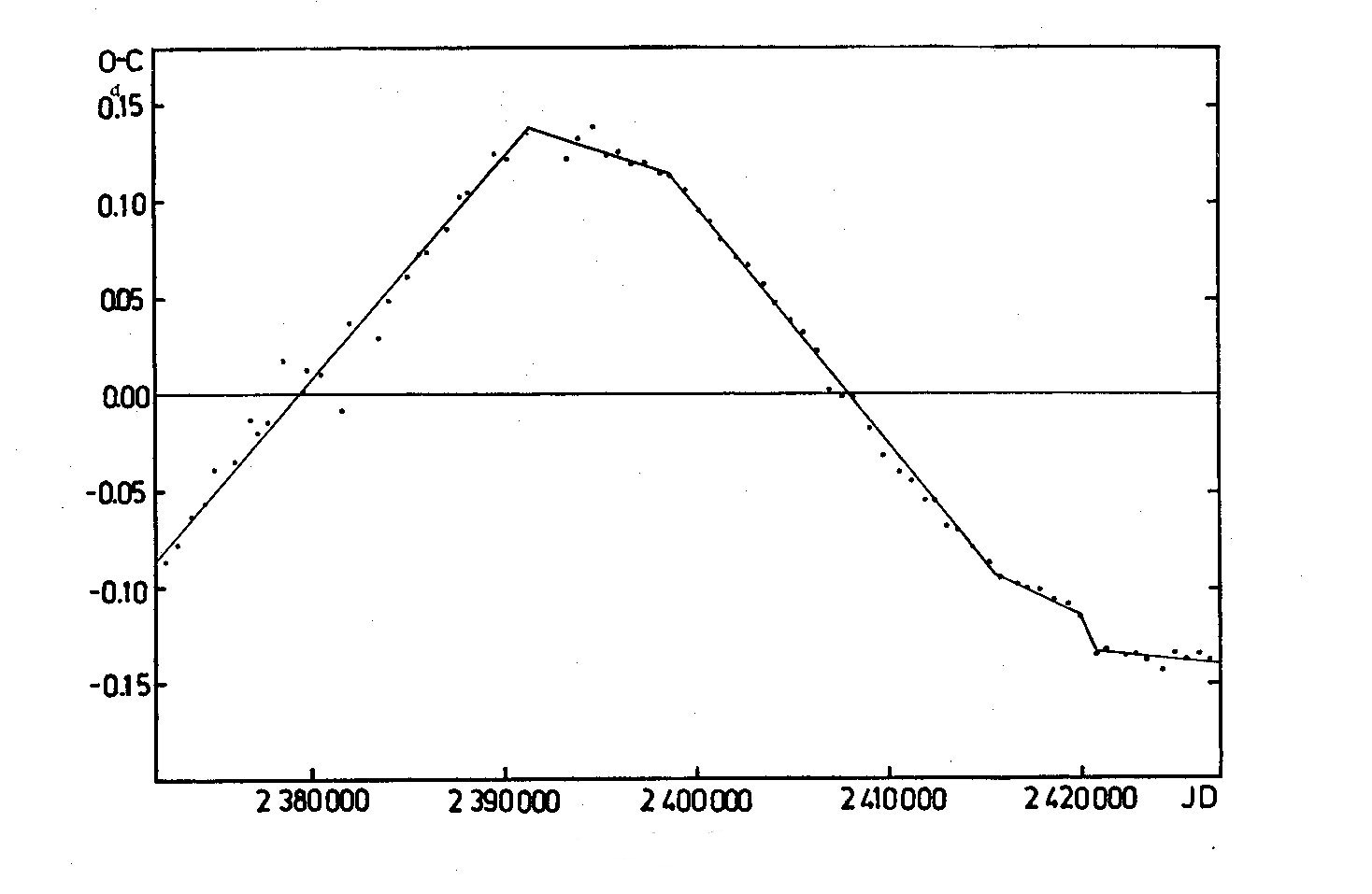

The obviously spurious periodicity of about 160-180 years length was an

understandable suggestion of the early observers: it was favoured by the

existence of two relatively long intervals of constant period. P_1 and P_3.

This led to the use of a mean period in the linear ephemeris formula

which, in its turn, gave rise to the characteristic wedge-shaped figure

in the O-C diagram, simulating the "first half" of a sine curve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2

This interpretation decomposes the great inequality into a series of

sudden period changes. Apparently they are forming a random set, the

changes occurring on an average once in 25-30 years. This is certainly a

non-periodic phenomenon, probably caused by discontinuities of the mass

exchange between the components or in the mass loss from the whole

system. Perhaps, the "overflowing" of the secondary component of its

Roche-limit is not a smooth phenomenon but it causes from time to time

directional outbursts of mass from the secondary, hereby changing the

eclipsing period in a sudden way.

The obviously spurious periodicity of about 160-180 years length was an

understandable suggestion of the early observers: it was favoured by the

existence of two relatively long intervals of constant period. P_1 and P_3.

This led to the use of a mean period in the linear ephemeris formula

which, in its turn, gave rise to the characteristic wedge-shaped figure

in the O-C diagram, simulating the "first half" of a sine curve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

DISCUSSION

Detre: Algol's O-C diagram looks rather like to one resulting from

cumulative effects of random period variations: on long cycles there are

superposed shorter cycles. How far is the 32 year period established?

Seitter: Irrespective of smaller errors having an effect on the period

length and the zero phase (and Hellerich's representation of the 32 year

period seems to be a very reliable one!), most of the jumps, especially

those rather thoroughly observed in 1944 and 1952, are quite well

established. This is mainly based on the fact that these two jumps

occurred within a time interval short enough not to be seriously

affected by any erroneous assumption concerning the 32 year periodicity.

Numerical data could certainly be shifted to some extent but the

existence of sudden period changes remains beyond doubt.

REFERENCES

Ebbighausen, E. G., 1958, Astrophys. J. 128, 598.

Ebbighausen, E. G., and Gange, J. J., 1962. Publ. Dominion Astrophys.

Obs. Victoria 12, 151.

Ferrari, K., 1934, Astr. Nachr. 253, 225.

Hellerich, J., 1919, Astr. Nachr. 209, 227.

Kopal, Z., Plavec, M. and Reilly, Edith, 1960, Jodrell Bank Ann. 1, 374.

Schneller, H., 1962, Mitt. Sternwarte Budapest No. 53.(CoKon N°.53)

Fig. 3

DISCUSSION

Detre: Algol's O-C diagram looks rather like to one resulting from

cumulative effects of random period variations: on long cycles there are

superposed shorter cycles. How far is the 32 year period established?

Seitter: Irrespective of smaller errors having an effect on the period

length and the zero phase (and Hellerich's representation of the 32 year

period seems to be a very reliable one!), most of the jumps, especially

those rather thoroughly observed in 1944 and 1952, are quite well

established. This is mainly based on the fact that these two jumps

occurred within a time interval short enough not to be seriously

affected by any erroneous assumption concerning the 32 year periodicity.

Numerical data could certainly be shifted to some extent but the

existence of sudden period changes remains beyond doubt.

REFERENCES

Ebbighausen, E. G., 1958, Astrophys. J. 128, 598.

Ebbighausen, E. G., and Gange, J. J., 1962. Publ. Dominion Astrophys.

Obs. Victoria 12, 151.

Ferrari, K., 1934, Astr. Nachr. 253, 225.

Hellerich, J., 1919, Astr. Nachr. 209, 227.

Kopal, Z., Plavec, M. and Reilly, Edith, 1960, Jodrell Bank Ann. 1, 374.

Schneller, H., 1962, Mitt. Sternwarte Budapest No. 53.(CoKon N°.53)

Fig. 1

The reliability of Hellerich's numerical representation of the 22-year

period is, of course, a basic question. Though small systematic deviations are

not to be entirely excluded, no serious error can, - in my opinion - arise

hereby. Especially the fact that the two jumps are rather close together,

separated by a quarter of the period only, means that the existence of

two sudden changes remains incontestable.

This somewhat perhaps surprising representation of the photoelectric

times of minima encourages me to an experiment: to apply a similar

procedure to the earlier measurements, too. Minima were observed since

1784 in a very great number. The overwhelming majority of these times of

minima is based on visual estimates, and their rather modest accuracy

(of the order of +-0.02d), doesn't permit a detection of the 1.9-year

light time effect. Besides, the in fluence of minor systematic errors in

the representation of the 32-year period will be considerably enhanced

by going back to the 18th century observations. This makes our proposed

representation to a tentative one; on the other hand the deviations from

a reasonable picture turn out relatively small, thus suggesting the

proposal I am going to discuss is not completely arbitrary.

Because of the large scatter of the individual epochs I used the normal

points meticulously derived by Ferrari (1934). Again, I subtracted Hellerich's

formula for the 32-year term. The residuals not only allow, they clearly

suggest a representation given by a polygon. The representation derived earlier

from the photoelectric minima is a continuation of this new polygon - the long

interval of constant period 1920-1944 can well be extended back to 1915.

There is no indication of a sudden period change in 1924 as it was proposed

by Schneller; the short sharp change around 1914/15 seems to be real (Fig. 2).

The following table summarizes this possible sequence of "events":

P_1 = 2.8673442d (1784)- 1835 (approx.) Delta P ~~-3.7s

P_2 = 2.8673012d 1835 - 1854 ~~-2.3s

P_3 = 2.8672775d 1854 - 1901 ~~+1.7s

P_4 = 2.8672967d 1901 - 1913 ~~-4.0s

P_5 = 2.8672506d 1913 - 1915 ~~+5.0s

P_6 = 2.86730807d 1915 - 1944 ~~+3.5s

P_7 = 2.86734862d 1944 - 1952 ~~-2.0s

P_8 = 2.86732442d 1952 -(1965)

Fig. 1

The reliability of Hellerich's numerical representation of the 22-year

period is, of course, a basic question. Though small systematic deviations are

not to be entirely excluded, no serious error can, - in my opinion - arise

hereby. Especially the fact that the two jumps are rather close together,

separated by a quarter of the period only, means that the existence of

two sudden changes remains incontestable.

This somewhat perhaps surprising representation of the photoelectric

times of minima encourages me to an experiment: to apply a similar

procedure to the earlier measurements, too. Minima were observed since

1784 in a very great number. The overwhelming majority of these times of

minima is based on visual estimates, and their rather modest accuracy

(of the order of +-0.02d), doesn't permit a detection of the 1.9-year

light time effect. Besides, the in fluence of minor systematic errors in

the representation of the 32-year period will be considerably enhanced

by going back to the 18th century observations. This makes our proposed

representation to a tentative one; on the other hand the deviations from

a reasonable picture turn out relatively small, thus suggesting the

proposal I am going to discuss is not completely arbitrary.

Because of the large scatter of the individual epochs I used the normal

points meticulously derived by Ferrari (1934). Again, I subtracted Hellerich's

formula for the 32-year term. The residuals not only allow, they clearly

suggest a representation given by a polygon. The representation derived earlier

from the photoelectric minima is a continuation of this new polygon - the long

interval of constant period 1920-1944 can well be extended back to 1915.

There is no indication of a sudden period change in 1924 as it was proposed

by Schneller; the short sharp change around 1914/15 seems to be real (Fig. 2).

The following table summarizes this possible sequence of "events":

P_1 = 2.8673442d (1784)- 1835 (approx.) Delta P ~~-3.7s

P_2 = 2.8673012d 1835 - 1854 ~~-2.3s

P_3 = 2.8672775d 1854 - 1901 ~~+1.7s

P_4 = 2.8672967d 1901 - 1913 ~~-4.0s

P_5 = 2.8672506d 1913 - 1915 ~~+5.0s

P_6 = 2.86730807d 1915 - 1944 ~~+3.5s

P_7 = 2.86734862d 1944 - 1952 ~~-2.0s

P_8 = 2.86732442d 1952 -(1965)

Fig. 2

This interpretation decomposes the great inequality into a series of

sudden period changes. Apparently they are forming a random set, the

changes occurring on an average once in 25-30 years. This is certainly a

non-periodic phenomenon, probably caused by discontinuities of the mass

exchange between the components or in the mass loss from the whole

system. Perhaps, the "overflowing" of the secondary component of its

Roche-limit is not a smooth phenomenon but it causes from time to time

directional outbursts of mass from the secondary, hereby changing the

eclipsing period in a sudden way.

The obviously spurious periodicity of about 160-180 years length was an

understandable suggestion of the early observers: it was favoured by the

existence of two relatively long intervals of constant period. P_1 and P_3.

This led to the use of a mean period in the linear ephemeris formula

which, in its turn, gave rise to the characteristic wedge-shaped figure

in the O-C diagram, simulating the "first half" of a sine curve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 2

This interpretation decomposes the great inequality into a series of

sudden period changes. Apparently they are forming a random set, the

changes occurring on an average once in 25-30 years. This is certainly a

non-periodic phenomenon, probably caused by discontinuities of the mass

exchange between the components or in the mass loss from the whole

system. Perhaps, the "overflowing" of the secondary component of its

Roche-limit is not a smooth phenomenon but it causes from time to time

directional outbursts of mass from the secondary, hereby changing the

eclipsing period in a sudden way.

The obviously spurious periodicity of about 160-180 years length was an

understandable suggestion of the early observers: it was favoured by the

existence of two relatively long intervals of constant period. P_1 and P_3.

This led to the use of a mean period in the linear ephemeris formula

which, in its turn, gave rise to the characteristic wedge-shaped figure

in the O-C diagram, simulating the "first half" of a sine curve (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3

DISCUSSION

Detre: Algol's O-C diagram looks rather like to one resulting from

cumulative effects of random period variations: on long cycles there are

superposed shorter cycles. How far is the 32 year period established?

Seitter: Irrespective of smaller errors having an effect on the period

length and the zero phase (and Hellerich's representation of the 32 year

period seems to be a very reliable one!), most of the jumps, especially

those rather thoroughly observed in 1944 and 1952, are quite well

established. This is mainly based on the fact that these two jumps

occurred within a time interval short enough not to be seriously

affected by any erroneous assumption concerning the 32 year periodicity.

Numerical data could certainly be shifted to some extent but the

existence of sudden period changes remains beyond doubt.

REFERENCES

Ebbighausen, E. G., 1958, Astrophys. J. 128, 598.

Ebbighausen, E. G., and Gange, J. J., 1962. Publ. Dominion Astrophys.

Obs. Victoria 12, 151.

Ferrari, K., 1934, Astr. Nachr. 253, 225.

Hellerich, J., 1919, Astr. Nachr. 209, 227.

Kopal, Z., Plavec, M. and Reilly, Edith, 1960, Jodrell Bank Ann. 1, 374.

Schneller, H., 1962, Mitt. Sternwarte Budapest No. 53.(CoKon N°.53)

Fig. 3

DISCUSSION

Detre: Algol's O-C diagram looks rather like to one resulting from

cumulative effects of random period variations: on long cycles there are

superposed shorter cycles. How far is the 32 year period established?

Seitter: Irrespective of smaller errors having an effect on the period

length and the zero phase (and Hellerich's representation of the 32 year

period seems to be a very reliable one!), most of the jumps, especially

those rather thoroughly observed in 1944 and 1952, are quite well

established. This is mainly based on the fact that these two jumps

occurred within a time interval short enough not to be seriously

affected by any erroneous assumption concerning the 32 year periodicity.

Numerical data could certainly be shifted to some extent but the

existence of sudden period changes remains beyond doubt.

REFERENCES

Ebbighausen, E. G., 1958, Astrophys. J. 128, 598.

Ebbighausen, E. G., and Gange, J. J., 1962. Publ. Dominion Astrophys.

Obs. Victoria 12, 151.

Ferrari, K., 1934, Astr. Nachr. 253, 225.

Hellerich, J., 1919, Astr. Nachr. 209, 227.

Kopal, Z., Plavec, M. and Reilly, Edith, 1960, Jodrell Bank Ann. 1, 374.

Schneller, H., 1962, Mitt. Sternwarte Budapest No. 53.(CoKon N°.53)